How Well Are We Actually Measuring Consumer Understanding?

How Well Are We Actually Measuring Consumer Understanding?

Consumer understanding has become a central regulatory concern in the UK, particularly under the Consumer Duty. Yet despite this heightened focus, there remains a substantial gap between what firms claim to measure, what they are actually measuring, and what regulators actually require evidence of. Many organisations believe their current methods for assessing consumer understanding are already accurate.

In practice, most are measuring proxies that say very little about whether consumers can meaningfully understand and use the information they are given.

This distinction matters. Financial and legal documents are not read for interest, they are read to support decisions that carry real consequences: financial loss, legal exposure, missed rights, or long-term detriment. Understanding, in this context, is not a stylistic property of the document. It is a cognitive outcome for the reader.

How misunderstanding causes harm in real life

In real-world settings, consumers must do far more than recognise information. They must:

- Infer consequences that are not explicitly stated

- Compare options using disclosed terms

- Apply information to their own circumstances.

- Anticipate future scenarios, such as missed payments or rate changes

- Act at the right time, in the right way

Failures at any of these stages can lead to poor outcomes even when disclosures are technically correct. This is where traditional metrics break down. They are document-centred, not human-centred. They assess whether information exists and appears readable, not whether it is intelligible or functions as intended in decision-making.

Regulators have increasingly made this distinction explicit. Firms are now expected to evidence consumer understanding, not assume it. Yet most measurement approaches were never designed to assess comprehension as a human capability. They were designed to assess text.

How firms typically measure “consumer understanding” today

Across financial services, insurance, utilities, and legal communications, a familiar set of practices dominates, such as:

- Readability scores are calculated

- Plain language and disclosure checklists are completed

- Mandatory information is verified as present.

- User testing confirms that people report the content as clear

- Often basic recall questions check whether users can remember facts

- Scenarios and open-ended questions are used to elicit explanations or decisions, but these are often shallow, loosely scored, and insufficiently tied to the specific judgments or actions the document is intended to support

- Use of large language models (LLMs) can support content generation, and some level of analysis. But they are not specialised compliance tools, nor an accurate predictor of understanding, and are likely to fall short for testing regulated communications (Amplifi, 2025).

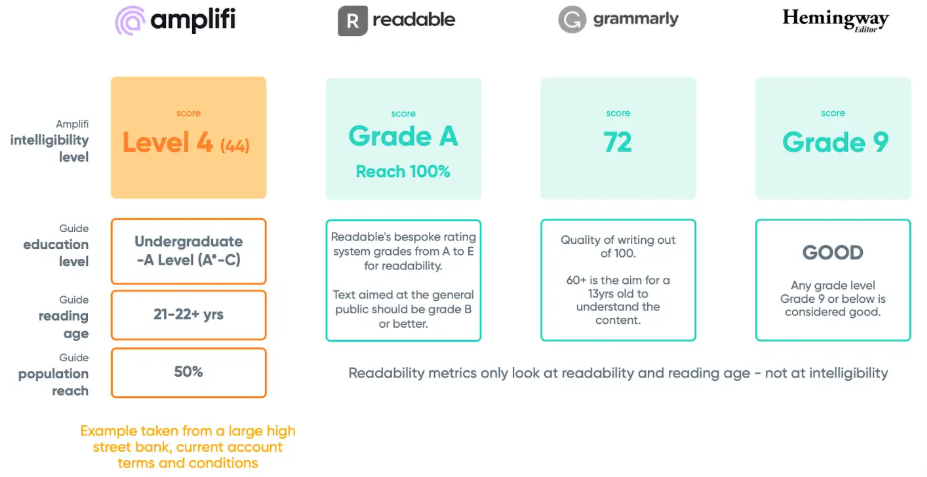

Readability, in particular, is often treated as a proxy for understanding. At its core, readability measures surface characteristics of text, such as sentence length, word frequency, or syntactic complexity (Chall & Dale, 1995). These measures are useful for identifying obviously dense or inaccessible language, and they play a legitimate role in improving baseline accessibility.

However, readability does not measure intelligibility or whether readers grasp meaning, interpret implications correctly, or apply information appropriately. A document can score well on readability metrics (see Figure 1) and still be widely misunderstood, especially where meaning depends on conditional rules, exceptions, trade-offs, or future consequences. In this sense, readability is a necessary but far from sufficient condition for understanding (Conklin, Hyde, & Parente, 2019).

Figure 1. Comparison of scores

Taken together, these activities create a sense of diligence and control. They also generate artefacts that are easy to document and audit.

What they do not reliably demonstrate is whether consumers can correctly interpret, apply, and act on information in ways that avoid foreseeable harm.

Why this is a construct validity problem

The central issue is not that firms are failing to measure consumer understanding.

In research terms, this is a construct validity issue (Straub, 1989). We say we are measuring “understanding,” but the tools in use largely capture adjacent constructs such as basic recall, confidence, or formal compliance. These are not the same thing.

Readability measures linguistic features, not meaning-making. A text can be short, familiar, and syntactically simple while still being conceptually opaque or misleading in context.

For instance, consider this statement:

“You must pay at least your minimum payment in sterling by the due date shown on your statement every month.”

This sentence is short, uses familiar words, and is syntactically straightforward. Yet it embeds multiple assumptions and potential misunderstandings. Consumers may not fully understand what counts as the “minimum payment,” whether paying in sterling is optional or restrictive, what happens if the due date falls on a non-banking day, or the consequences of paying late or paying slightly less than required. None of these issues are visible to readability measures, yet each is critical to correct interpretation and action.

Disclosure checklists confirm presence, not uptake. They tell us that information exists in a document, not that it has been noticed, interpreted correctly, or how it can support informed decision-making.

Self-reported clarity measures perceived understanding, not actual capability. Confidence is a notoriously poor proxy for competence, particularly in complex domains where consumers often over estimate their capabilities.

Recall testing measures memory, not comprehension. Consumers can often repeat definitions or figures while still misunderstanding implications, trade-offs, or conditional consequences. For instance, true or false questions, like those used in an FCA study, primarily assess recognition and recall rather than an applied or decision-relevant understanding. They are highly sensitive to guessing behaviour, do not capture partial understanding, differences in confidence, and prior familiarity with institutional concepts.

Even scenario-based testing, when used, is frequently underpowered. Scenarios are often generic, scoring criteria are vague, and success is judged on plausibility rather than correctness.

As an Example, consider a comprehension question from Faireer Finance:

“If you miss a repayment, will your interest-free offer be withdrawn?” Participants are shown the relevant terms document and then must locate the relevant clause and answer the question based on what it says.

While questions of this kind are directionally right, they are not sufficient. They improve on surface-level measures but still fall short of capturing consumer understanding as a multi-level, outcome-relevant construct. Without being embedded in a structured framework that separates recognition, interpretation, application, and decision-use, they risk becoming another proxy measure that feels robust but offers limited diagnostic or regulatory assurance.

Crucially, they are rarely anchored to the real decisions and actions that the document is meant to support. Nor is this used for diagnostic purposes.

Each of these measures has some value. The problem arises when they are treated as evidence of understanding itself.

They are proxies, and weak ones, when they are used as substitutes for direct measures of comprehension, they create false assurance.

Implications beyond measuring “understanding”

The problem of construct validity goes beyond where consumers technically “understand” legal or regulatory information. In simple terms, construct validity asks whether a measure truly captures what it is meant to capture. This means asking whether the tools, tests, or indicators being used actually reflect the real-world concepts they claim to assess.

When there is a mismatch between intention and measurement, the consequences extend beyond user understanding. Measures designed to assess compliance, fairness, or clarity may instead capture surface features such as familiarity or the ability to recall information. As a result, conclusions about broader goals can be misleading.

This same misalignment affects outcomes such as trust and transparency. If regulatory bodies rely on measures that do not genuinely reflect how people experience or evaluate legal information or processes, claims about increased trust or improved transparency may not correspond to reality. In this way, weaknesses in construct validity can undermine not only individual assessments but also the credibility of legal and organisational decision-making.

Measurement of Trust

Trust is frequently inferred from satisfaction scores, brand sentiment, or stated confidence. These indicators primarily capture affective responses, familiarity, or general attitudes toward a firm. They do not establish whether trust is informed by an accurate grasp of product features, risks, limitations, or obligations through legal communications. In practice, a consumer may express high trust precisely because they have not fully understood the downsides, conditions, or trade-offs associated with a product.

When trust is measured without reference to comprehension, it becomes a weak and potentially misleading signal. High trust scores can coexist with systematic misunderstanding and poor decision-making, creating false reassurance for firms and regulators. Rather than mitigating harm, such measures may obscure it by suggesting positive consumer outcomes where informed reliance is absent. Therefore, trust, like understanding, must account for how consumers interpret and use information, not just how they feel about an institution.

Measurement of Transparency

Transparency faces a similar challenge. It is commonly evidenced through disclosure volume, visibility, or compliance with information requirements. Information can be fully disclosed and still fail to make its implications clear, salient, or actionable. The draft guidance on Unfair Contract Terms recently released by the CMA makes this point:

“Transparency depends not only on the words used but also on how the contract is structured and presented” and “whether the average consumer is likely to understand the meaning and practical effect of the term.”

CMA Draft Guidance on Unfair Contract Terms, Chapter 4.

Credit card agreements provide a familiar example. These documents typically contain all the information required by law such as: interest rates, minimum payments, fees, conditions for promotional offers, and consequences of missed payments. From a disclosure perspective, they are often exemplary. From an outcomes perspective, they are frequently ineffective.

Measuring transparency without testing whether consumers can identify, interpret, and use the information risks conflating openness with effectiveness.

The broader lesson is that outcome-based measures cannot be evidenced through surface features or indirect proxies. If firms are serious about demonstrating trust, transparency, or consumer understanding within an outcomes-focused regulatory regime, their measurement approaches must align with the underlying cognitive and behavioural realities of those measures. Without that alignment, assurance rests on signals that appear robust but fail to capture how consumers actually interpret, apply, reflect, and act on information in practice.

Implications for firms and regulators

Reframing consumer understanding as a construct validity issue changes the assurance conversation. The focus shifts from whether communications are readable or compliant to whether they are intelligible and function effectively for real people making real decisions.

The relevant questions become:

- Where does harm arise when understanding fails for this product and target audience?

- Which dimension of measures best captures comprehension in this context?

- How should these dimensions vary with risk, document purpose, and consumer diversity?

- Where do results show breakdowns, and which interventions address each level?

- Do outcomes hold across vulnerable and lower-literacy groups?

- How will evidence feed into governance, redesign, and continuous improvement?

Click here to view Amplifi’s Multi-Level Comprehension Framework©